home > projects and works > fake 2005 > the book - contents

- - - <de>

Institutionalized resistant places – thematic park anarchism

Between alternative culture and touristy spot

Translated from German by Alain Kessi

Picture 1: Grounds of the Red Factory

Since the 1980ies the grounds of the Red Factory [1] in Zurich have been a place that was well-known far beyond the city boundaries. Due to the history of its origins it is a legendary place – but also a place that raises many questions. The opening of the Red Factory for youth culture, art and alternative ways of life was imposed by struggles against strong reservations from the side of official city politics, in order to provide a space for a practice of resistance and resistant culture. The inception of this free space in a city like Zurich, which is rather lacking in resistant places, is on the one hand a historical merit – on the other hand the question arises to what extent the original high aims can still be fulfilled in a spatially assigned, subsidized and in the meantime institutionalized situation. The dichotomy of the Red Factory between resistant place and touristy spot becomes apparent if we read the entries in travel guides. For instance, the German life-style and scene magazine MAX writes in its online-city-guide-zurich: “A remainder of the wild 80ies when Zurich’s avant-garde art still had to struggle for its niches with riots. At the time, there were also demonstrations against the demolition of the silk factory built 1892. These were successful: Now a popular alternative cultural center is located in the distinctive brick halls, in self-management: music stage, theater hall, gallery and a number of working groups – from which the Swiss alternative culture scene takes its new recruits. A program every night! The heart of the Factory is the cozy self-service canteen at the lake.” [2] The free space of the Red Factory has in the meantime been incorporated into the interests of the city’s image strategies and tourism industry. It is a touristy spot and a place of alternative culture at the same time. How can the two be reconciled? Just recently there was another nice example of how alternative practices and spectacle can clash. The Red Factory is sprayed with many graffiti, some of them historical almost, others the work of a newer up-coming generation (Picture 1). In June this year the project “Graffiti Jam” invited many international graffiti artists to reshape the grounds. To this end, all the buildings and all the graffiti on the grounds were first painted over in the original brown-red color of the bricks (Picture 2). The company that had been recruited as a sponsor for this event and provided the necessary special paints is specialized in impregnations of buildings and graffiti removal. Graffiti, originally a means of self-empowerment in the urban space, are in this case robbed of their resistant potential. They are being reduced to their aesthetic surface, and in the temporally and spatially limited event they become a gesture, a spectacle that can be institutionalized, steered and commercialized. In this context one could speak of a fake – thematic park anarchism.

Picture 2: Preparations for the “Graffiti Jam” in June 2005

The Shedhalle is also located on the grounds of the Red Factory. [3] With the thematic series of projects “Spectacle, the Pleasure Principle and the Carnivalesque?” an exhibition project in three consecutive chapters started in fall 2004. Strategies of activist practice were examined, and the locations where these practices take place analyzed. Activist artists and artistic activist (there is a fine line between them) explored to what extent the “Carnivalesque” can be a creative strategy or an effective method for presenting and articulating political aims, or whether only spectacular surfaces are produced. The starting point of the project on subversive production of meaning was a re-reading of the writings of the Russian literary scholar Michail Bakhtin. In Literature and Carnival, [4] Bakhtin analyzed the influences of the medieval culture of laughter and the Carnivalesque in popular customs on literature. His theory of the novel assumes that the Carnivalesque offers a possibility to “turn the world inside out and thus to repeal the order and all forms of fear, reverence, piety and etiquette arising from it.” Laughter and the Carnivalesque for Bakhtin are forms of protection which allow to undermine at least temporarily external and more importantly internal constraints and censorship, and symbolically to portray a non-hegemonic truth which “opens the world in a new way.” Seen from this angle the Carnivalesque, through the temporary absence of power and the re-conquest of the public space, can be appropriate for articulating something like a “world view from below” and taking on the character of a counter-culture as well as enabling to relativize the established order.

Picture 3: Video still from Müller-Sendung (“Mueller Broadcasting”),

CH-Magazin, DRS, 1980

In this context it seemed interesting to us to have a look at the so-called youth uprising [5] of the early 80ies in Zurich, which – as mentioned already – have led to the establishment of the Red Factory. It was in this time that the demonstrators developed forms of protest which in our opinion could well be termed “carnivalesque.” On the one hand they succeeded with playful, subversive provocation to inscribe themselves in mediatic communication cycles. On the other, they have demonstrated a new form of “Streitkultur” (culture of debate). A prominent example of these forms of protest is the “Müller-Sendung,” or Mueller Broadcasting (Picture 3). Due to the youth uprising the CH-Magazin, a televised round-table discussion on Swiss television, invites, next to the chief of police, members of the city council and the president of the city’s Social-Democratic Party, two representatives of the youth movement to its discussion. The two “movementers” enact the upright married couple Anna and Hans Mueller. They demand a tougher police intervention against the rioters. This inversion disrupts the usual controversial pattern of discussion, and robs the representatives of the city of their arguments. Their rhetoric is exposed, and their points of view appear ridiculous. The speakers’ roles are swapped, which turns the round-table discussion into a mass-media farce in front of the running cameras. A further example of a carnivalesque strategy from that time is the “swimming demo”: A demonstration in the streets in the public space of the inner city of Zurich is banned. In answer to this the protesters relocate the demonstration into the water of the Limmat river between the Quai Bridge and the Platzspitz. The public space, in this case a city river, is squatted outside of the established conventions. Camera teams, the police and the population only watch in surprise.

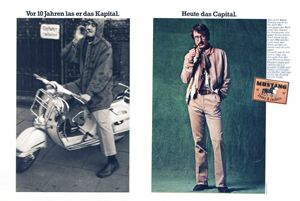

Picture 4: Rudi Maier, Advertising from the exhibition “Narrenproduktion”

(Jester Production), 1st Chapter of the thematic series project

“Spectacle, the Pleasure Principle and the Carnivalesque?”, Shedhalle 2004.

If we look at such examples, or newer ones like the “Global Carnival Against Capitalism” (18 June 1999, on the occasion of a G8 Summit in Cologne, Germany), it becomes evident how in a political context carnivalesque moments are used that on the one hand create commonality, arouse the curiosity and pleasure to deal with a given political approach, occupy public and media space, but on the other are also in danger of being reduced in their reception to a superficial media spectacle. In a society of the spectacle, of many events and festivals, it is at times difficult to distinguish whether a commercialized society of the strong impressions is using carnivalesque strategies or whether the subversive potential is able to articulate clear demands that are received as such. In this field of contention the Carnivalesque is used on the one hand as a resistant practice – on the other, it is instrumentalized as a regulating valve by the capitalist interests through commodification, regulation and institutionalizing of social desires. The general dichotomy of the potential of pop-cultural phenomena for self-empowerment raises the question to what extent our society follows both a consumptive principle and a resistant principle of the Carnivalesque. Presumably, the two concepts draw from each other and influence each other and mix. The fact that the political is increasingly turned into a spectacle demands a positioning. An interesting question is what role art or the aesthetic practice plays in this, given that it is itself concerned by this principle. Reflections on the aesthetization of the Carnivalesque or the carnivalization of the aesthetic are therefore important: To what extent is an artistic practice also carnivalesque in the sense of a resistant practice? The artistic practice is interested in carnivalesque strategies like the ones used in media guerilla and guerilla communication: On the one hand it analyzes them and comments on them, on the other it often finds in them a language with which to call the attention to explosive social themes and initiate discussion.

What now are the places of the Carnivalesque and what are the stages of the spectacle? Or do they overlap completely? Matthias Rothe and Hartmut Schröder [6] propose to read, with Bakhtin, also counter-placements or counter-sites [7] as carnivalesque spaces. From this point of view the Red Factory would be a carnivalesque place. Carnivalesque in the sense that on the one hand it constitutes a counter-place, on the other it cannot do without forms of spectacle in order to be perceived publicly. The place between these two poles needs to be ever again renegotiated. Any standstill bears the danger of institutional stagnancy and the integration of your own repertoire of signs into commercial usage interests (Picture 4). [8]

Notes

| The Rote Fabrik (Red Factory) was built in 1892 as a mechanical silk weaving mill based on plans by the architect Carl Arnold Séquin. After it had changed hands several times and been sitting empty for some time, the city of Zurich bought the Red Factory with the intention of demolishing the buildings to make place for increasing the width of the neighboring Seestrasse (Lake Road). But the Office for the Protection of Cultural Heritage as well as the Social-Democratic Party successfully intervened against these plans with a popular initiative. The Factory was to remain and be turned into a culture and leisure center. 1977 the voting citizens charged the City Council with working out a proposal for the use of the Red Factory as a cultural and leisure center. Three years later the youth uprising of the beginning of the 80ies accelerated the creation of the alternative cultural center “Red Factory.” |

[2] Available on <http://www.max.msn.de/cityguide/zuerich/tipps.html?id=851134>. [Accessed 7 August 2005]

| The Shedhalle is located on the grounds of the Red Factory. It was created at the instigation of an interest group of local artists who were underrepresented in the established art system. Disputes between the artists and the collective running the Red Factory later led to a situation in which 1986 the Shedhalle split off from the organization of the Red Factory and founded its own association. After 1994 there was a so-called “curatorial rupture.” The overall aim of this change was to open the program for less conventional forms of mediating art, and for interdisciplinary collaborations with other social and scientific organizations. In order to live up to this goal the team was to be composed of collaborators who are already active at the interstices of art, discursive intervention and political engagement. Among the curators there were Renate Lorenz, Silvia Kafehsy, Ursula Biemann, Marion von Osten, Justin Hoffmann, Elke aus dem Moore and Frederikke Hansen. A feminist orientation and a program based on social politics define the curatorial practice. |

[4] Cf. Bachtin, Michail: Literatur und Karneval. Zur Romantheorie und Lachkultur (Literature and Carnival. On Novel Theory and Laughing Culture, a selection in German from two of Bakhtin’s works, published in English separately as Bakhtin, Mikhail: Rabelais and his World, Cambridge: M.I.T. Press 1968; Bakhtin, Mikhail: Problems of Dostoevski’s Poetics, Ann Arbor: Ardis 1973), Frankfurt/Berlin/Wien 1985.

| The uprising began in Zurich with the so-called “Opera House Riot” on 30 May 1980. Under great personal engagement and free from any institutional constraints the activists of the Videoladen Zürich (Video Shop Zurich) filmed the movement from the inside, so to speak. Out of the varied material at the end of 1980 the film Züri brännt (Zurich is burning) was made. The film documents of this time were collected by the video archive City in Movement. A total of 111 video tapes were collected, referring to the cultural awakening of the youth uprising of the 80ies, as well as their effect on the early 90ies and their artistic surrounding. Extracts from: Heinz Nigg, Express yourself – Sturm und Drang: Bewegungsvideo (Express yourself – Storm and Stress: Movement Video), in: Wir wollen alles, und zwar subito! Die Achtziger Jugendunruhen in der Schweiz und ihre Folgen (We want everything! Now! The Eighties Youth Uprising in Switzerland and Its Consequences), Zürich 2001. |

[6] Matthias Rothe/Hartmut Schröder: Thematische Einleitung: Vom Tabu zur Tabuverletzung (Thematic Introduction: From the Taboo to the Taboo Breach), in: Matthias Rothe/Hartmut Schröder (Hrsg.): Ritualisierte Tabuverletzungen, Lachkultur und das Karnevaleske (Ritualized taboo breaches, laughing culture, and the Carnivalesque), Berlin-Frankfurt/Oder, pp. 11-15.

[7] They are referring to Michel Foucault, Of Other Spaces (1967), translated from the French by Jay Miskowiec, available online on <http://www.foucault.info/documents/heteroTopia/foucault.heteroTopia.en.html>. [Accessed 7 August 2005] – translator’s note.

[8] Rudi Maier, Mediologische Vereinigung Ludwigsburg (Mediological Association Ludwigsburg): Narrenproduktion - Zur Disziplinierung der Zeichen der Revolte (Jester production – On the disciplining of the signs of revolt).

“Get up, stand up,” “Fight for your right!,” “Radicalize life!” – Long-time slogans of leftist movements and at the same time headlines of commercial advertisings of the last few years. They show a contentious relation which has been visible since 1967 and in which advertisings intend to discipline the signs of revolt and label the bearers of revolt as jesters and Other. The advertisings, which are often designed in playful modes, give much away about the order of the respective social formation from 1967 to this day – a multimedia introduction to the field of “Advertising & Revolt.”