home > projects and works > fake 2005 > the book - contents

- - - <exhibition>

"women and queeries speak up"

- attempts to create feminist and queer media spaces…

in films like "monika m." and "pashke and sofia"

"monika m." and "pashke and sofia" are examples for portraits of 'women' and about those situated in a queer position in different societies and communities – a useful way to create a space for a feminist and queer critique that is much too often left out in mainstream and also alternative media? can portraits like "monika m." and "pashke and sofia" be understood as a sort of speaker’s position that is a personal and emotional standpoint with strong political and social impacts?

the context for producing "monika m." was a compilation commissioned by the german-austrian-swiss tv-station 3sat about the german election campaign 2002. within this format people working for campaigns of political parties were meant to be portrayed. the protagonist that i chose is monika m.: she is not working for a party but she claims political and social abuses in very strong speeches and she is also ready to fight for her convictions. at first it seems there is no audience for her performances but the viewers sooner or later realize that the topics pointed out by the protagonist are in fact related to their own reality and that "monika m." is speaking to every viewer on a personal level. sexist construction of gender roles, sexual abuse in heteronormative nuclear families, the western capitalist concept of work and consumption and social injustices - all seen in a steady deadening repetition and articulated in a mixture of serious political critique and humorous sarcasm.

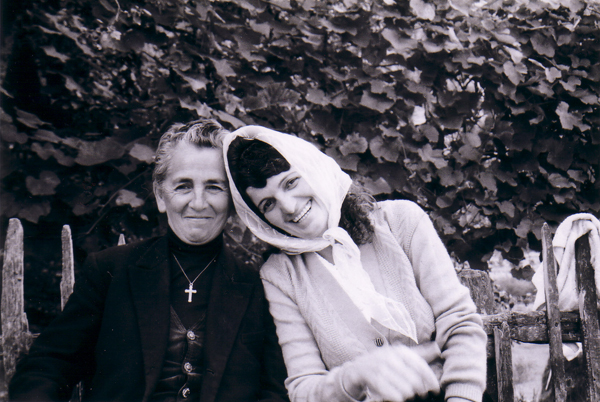

from a different point of view, namely that of northern albania, pashke and sofia are also talking about the construction of gender roles.

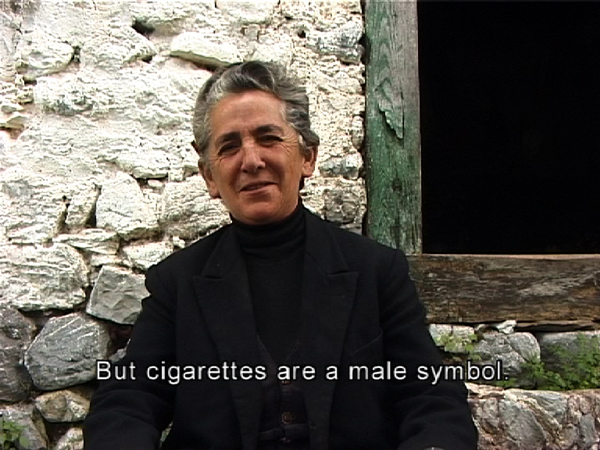

pashke (62) has chosen to live as a "sworn virgin" at the age of 30, whereas sofia was married and has 6 children.

northern albania has a long tradition of “sworn virgins” - and this tradition is based on a law called "kanun" which got into conflict in times of communism, which can be partly seen in an extract of the film “rruga e lirise” (by esat muslin, script: natasha lako). aside from the meaning that "sworn virgins" stabilize the patriarchal system, because "sworn virgins" shall take in the so-called man's role in order to rule the house and the family when there is no man to do it, being a "sworn virgin" gave women the chance to avoid a forced marriage. for pashke it also meant that s/he could stay in her/his own house after her/his uncle had died and to have her/his own land and sheep. also it gave her/him the right to vote and the possibility to move between the village and the city on her/his own.

being a “sworn virgin” is not the same as being a man in albania, but it gives you some of the rights that men have and that women don’t have.

who is getting which resources, who is able to get education and to work for money - these are some means to question various forms of hierarchies and discriminations that are clearly gender related. especially in the rural areas of northern albania, it still seems to be the rule that if you are a man, you not only are the one who inherits in the first place. you are also the one who can go find a job and earn money or who can leave the country to make a living in italy or some other country – living conditions and possibilities that are still often out of reach for women.

but aside from these contexts it becomes obvious that pashke seems to have a desire for masculinity that is not only related to a social need. and even though an outsider gaze on countries like albania makes not really sense because the ways in which gender roles are constructed and lived have definitely to be seen within the context of each society. but it may still be possible for the audience to relate to pashke and also sofia when they are talking about these gender aspects and avoid an exotisation of them.

and it is of course the genre of documentary films that is to be questioned after all. can performances like pashke's when s/he is presenting his/her sheep and ironizing the maleness of the ram in the herd in saying, “remain standing! be a man!” or when s/he is talking about wearing a cigarette behind her/his ear to perform maleness but not being a smoker, intervene the construction of gaze that is made by the film team and the audience? or can the one-dimensional hierarchy of gaze be interrupted when sofia returns the gaze to the filmmaker behind the camera in asking her “do you have more freedom because you’re dressed like a boy?”?

it is these kinds of questions of feminist and queer standpoints and the negotiation of these topics not only as a secondary area of confrontation or marginal matter, but as part of every other reflection of societies, communities and relationships and as one of the main challenges in creating cultural products that possibly disclose hierarchies and discriminations.