Get Real with WeAreTheArtists!

Modes of communication against a loss of reality in the professional art establishment

translated from German by Alain Kessi

Contemporary art is inherently in a permanent condition of latent instability. On the one hand, this is grounded in the subjectivity of aesthetic judgment. On the other, in the expectation of novelty towards the art work; after all, a necessary aspect of the new is that it contains something to which there is no reference and for which there are no standards. This may be the reason why the protagonists of the art system often react with an increased need for objectivity and professionalism, even if they have to admit in the end that interpretational or conceptual legitimizations can be found for nearly all exploration of form.

This set of problems by no means applies to the sole art system. The objective comprehensibility of the motivations and judgments plays an important role in all social spheres, but at the same time it has become more and more a farce. Paradoxically this is related to the consequences of furthering professionalization and lies in the banal fact that nowadays ever fewer people in ever fewer spheres are able to critically assess a piece of information. Important decisions are made by experts and specialists who can claim for themselves that they know something about the issue; due to lack of knowledge all others are often not even conceded the right to formulate a criticism of it.

Ultimately a successful decision finding by experts relies on the assumption that the few decision makers firstly are the best qualified people, and secondly decide in a professional manner. As a qualification one might add that the society has not only professionalized itself content-wise, but also structurally; in this context this means that it is not necessarily the people most versed in a given field who become the decision makers, but rather those who understand and are able to use the dynamics of the path leading there. It has become an open secret that it is not always professional, but also social and strategic competency that ultimately define the effective decision makers.

Speaking of professional decisions as such, it should be noted that nobody is free of personal arbitrariness, preferences and resentments: The less opinions are allowed into a discourse, however, the more the results become dependent on these influences. Ironically the result of professionalization is a state in which professional decisions are by no means reached through professional competence, but to a degree at least as large through the personal arbitrariness of a privileged minority.

Just like law, politics, religion and science, art as a social subsystem cultivates a specialized discourse in which only those are admitted who are recognized by the system in terms of their education and qualification. Internally to its system, art structures itself in various spheres of production, distribution and reception, to which artists, curators, critics and other art mediators, lecturers, collectors and gallerists participate instructively. The various professional alleys, or perhaps better: roles which have developed within the art system, are by no means clearly separated from each other, let alone independent; rather, upon a closer look art appears as a widely ramified mesh of various interdependencies.

As a consequence of the budget pressure of the media, a journalist or art critic is barely able to live from writing alone, and therefore acts at the same time as a teacher, curator or art expert. The appointment as an art expert however, to take just one example, depends on being proposed by others, and that often means those who based on their professional position would in fact be the first choice as experts but for the same reason do not have time and therefore propose someone else. As a consequence of this, if you are an art critic you’ll sometimes think it over twice whether to write a negative review about a show: what if the director of the corresponding museum shortly after that is going to propose someone for work on a jury of experts?

Then again as a curator, for realizing projects you are often dependent on money from foundations, on whose board are other curators and artists; however little good you may think of the oeuvre of an artist, you’ll beware of communicating this publicly in certain cases. You might even consider inviting such an artist to participate in an exhibition, especially if you suspect him to be a member of the board reviewing candidates for the next curator’s post you aspire to.

It is also hardly surprising if artists who strive for a gallery connection maintain a courteous tone with the gallerists. Curators hoping for connections with rich collectors do the same: bearing in mind how the kunsthallen and art associations nowadays chronically struggle with insufficient budgets, they don’t have much of a choice.

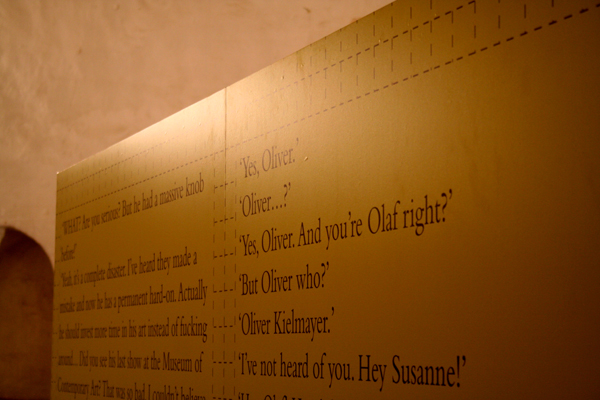

All the protagonists within the art system are thus parts of a subtly and broadly ramified mesh of interdependences characterized by a precautious and considered way of dealing with each other; like a game in which each is trying to keep as many options open for themselves as possible. It is perfectly common to praise, in the afternoon during a jury meeting, the broad acceptance and success of an artistic position, in the evening among friends however to vehemently question why this very same position is successful at all; only in an intimate circle is it possible to seriously question the quality of a recognized work or even to admit that one does not personally find any value in it. No doubt the public restraint contributes to preventing emotional overreaction as well as guaranteeing a certain degree of decency. But the cautiousness in expressing opinion does not belie the fact that there is a quite real exchange of opinion, even if only within small, intimate networks.

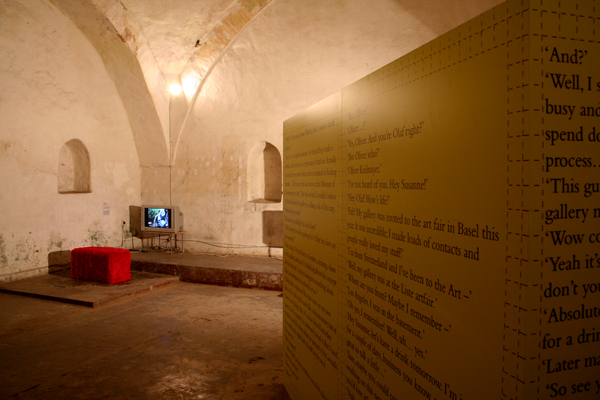

It is such mechanisms and the resulting schizophrenias that form the ground for projects like WeAreTheArtists. WeAreTheArtists was founded in 2004. The original idea was to make visible and accessible a continuously growing network of curators, art mediators and especially artists. This concretely meant to make an attempt to foster the communication taking place within the network and at the same time to communicate it to the outside via a free newspaper as well as a home page. In opposition to the conventional reporting in which the arbitrary often hides behind professional motives and is communicated to the public dressed in a professionally made and objectively true decision, the communication was to be direct and real.

The wish to make visible personal motives and motivations as well as the corresponding subjective arbitrary of the protagonists within the art system is not only legitimate, but downright necessary. This is not about a utopia of abolishing the arbitrary, but rather about making the arbitrary visible as such and through this to expose it to criticism. The reason why this is so important, nowadays more than ever, has to do on the one hand with the degree of maturity of the abovementioned development, on the other with the suddenly reigning global perspective. In a locally operating community, those involved disposed of a kind of background knowledge that enabled them to assess the professional reporting, if only due to the immediacy of the events and the familiarity with the persons who have left their stamp on them. On the global scale this familiarity has been lost, and the information presented can barely be put into context or falsified based on one’s own better knowledge. This puts new requirements to a meaningful reporting about art. Professional art criticism remains an important form of communication about art, but it can hardly be the only one.

In communicating subjective perspectives of artists, curators and art mediators as well as producing corresponding formats, there may lie an opportunity for a corrective opposing the subjective arbitrary to all decisions legitimized by professional behavior. In many other areas the deficiency of professional discourses including their respective formats of communication and the corresponding wish for authenticity have already led to a turn towards the ordinary and subjective. In recent years it is mainly television that has been successful at generating formats that allow a corresponding communication. With reality TV a new, separate genre was even created. A glance at the more recent history of television is exciting not only in terms of the development of new formats of communication, but at the same time with respect to the limits it makes apparent.

At the beginning of the 1980s television series like ‘Dallas’ or ‘Dynasty’ still made a splash, but already towards the middle of the same decade the accent shifted to the reality of the average citizen. On German-language television ‘Lindenstrasse’ was launched in 1985. Quite the opposite of ‘Dynasty,’ which was difficult to surpass in its artificiality, ‘Lindenstrasse’ represented the ‘normal’ life in a German city. Like its English counterparts like ‘Neighbours’ or ‘Eastenders,’ it still resorted to professional script-writers and actors, but soon after the so-called reality-TV formats made their appearance, which either reconstructed a true story with actors or eventually did completely without actors and replaced them with ‘normal’ people. In ‘The Real World,’ broadcast by the American station MTV from 1992 onwards, apparently randomly selected people were brought together in an apartment-sharing community and continuously filmed for 18 hours a day. The entire ‘Big Brother’ seasons, which started 1999, continue to follow this example. What’s interesting is that the turn to reality was merely a first step, and that meanwhile reality itself is in turn being staged. If the first season of ‘Big Brother’ was still based on bringing together a variety of personalities in an apartment, now an entire village is being built, where the participants move in for a period of time not defined in advance. This may make the conditions of life together more real – in that the inhabitants no longer find themselves in a prison-like imposed community which would never come about in real life – but at the same time also more artificial, since a copy of the entire setting present in real life is being built up.

At the same time the candidates who are willing to participate in such broadcasts have more and more turned into actors. This simply means that reality-TV, created out of a need for more reality, ends up not communicating any reality, but on the contrary manipulates reality through forms of telegenic representation. The self-representation mentioned above is thus not only symptomatic of a social trend, but also a hint that precisely reality formats can under certain circumstances promote representation and staging.

Although the various reality-TV formats reflect the wish for authenticity which is latently present in the society, they cannot really live up to it. On the one hand this is linked to the reversal effect described above, in which reality suddenly becomes itself represented, and on the other with limitations given by the functioning of the respective system of references. The mere fact that this is a TV broadcast entails so many limitations and requirements that in the end, reality cannot but be broadcast in a prepared form. The selection of appropriate ‘normal citizens’ for a TV broadcast in itself does not mirror any reality, but is the result of thoughts on what mix will guarantee the greatest frequency of friction and scandals – in other words: audience ratings.

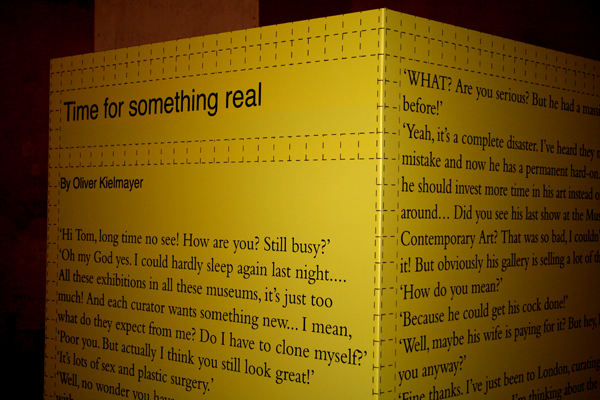

Even a project like WeAreTheArtists finds itself in the field of contention opening up between the wish for authentic communication and the limitations imposed by the medium of a given system. In the case of the newspaper of WeAreTheArtist, the starts unspectacularly with the fact that it has a certain size and it could possibly happen that not all texts will fit unabridged. Despite the claim that the contributions of the artists will be neither proofread nor edited, the editor is sometimes forced to abridge them, which necessarily entails a certain censorship. With respect to people’s names appearing in personal accounts, the reality format also collides with the medium it draws upon. Despite the global perspective the local dynamic continues to be valid, and so the persons appearing in the text are very likely to recognize the authors. The use of initials or pseudonyms only marginally mitigates the situation, while it constitutes at the same time a significant compromise in terms of the authenticity of the reporting. Not only names mentioned can be iffy, but also content. Mere seemliness and the respectful approach to other people forbid publishing many a conversation that spices up an opening. Authentic communication tends to be not only direct and merciless, but at times just plain offensive.

The authors of WeAreTheArtists cannot but remain nodes in the web of interdependencies of the art system. That’s precisely why their stories are exciting. The danger that like in reality-TV the wish for more authenticity ended up in a manipulation is definitely present here, too. This is not to say, however, that a communication representing reality cannot in the end just as well generate true statements. How well reality formats function in art, whether they are more than a fashion trend and work out as part of the mediation of art, only time will show.