code flow - e-texts

Vector Magazine 03/2006

Vector Magazine 03/2006

Iaşi, Romania

“The Future is Stupid” (Jenny Holzer) [1]

Future: I saw a field full of sunflowers. They were all looking the wrong way. (Dan Perjovschi) [2]

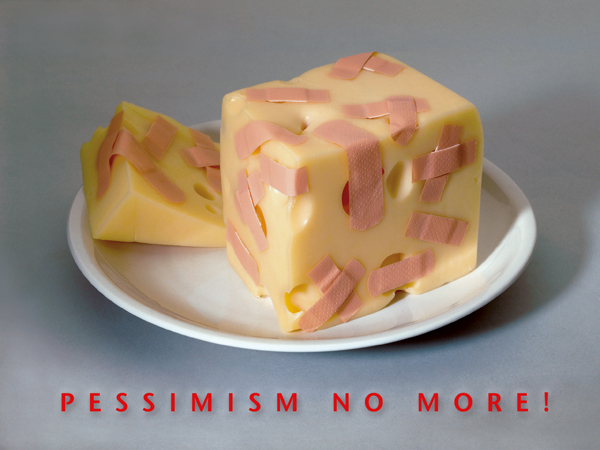

Pessimism no more [3] – exoticism is everywhere [4]

Back to reality, or

Micro-approaches for handling institutional matrices in the local art context

the 21st century

2007-02-08

Pessimism No More!, 2002, Billboard, 300x400 cm (dimensions variable). Part of the group show

“Bound/less Borders,” Belgrade, Yugoslavia; Cetinje, Montenegro; Bucharest, Romania; Vienna, Austria

(concept of the show: Biljana Tomic). © Pravdoljub Ivanov

In a post-colonial situation and a growing economy of services, in a reality broadened by new technologies, the essence and structure of artistic life is changed, and with it the discourse about the museum. Theoreticians like Nicolas Bourriaud write manifestos about saying good-bye to the era of the isolated geniuses and embracing a time of relational aesthetics. [5] The newly emerged artistic practices give a rendering of the collective wishes of the society.

No more reality! The Demonstration. © Philippe Parreno

If in 1989, the East declared “No more ideology!” and went about rediscovering its reality, the West announced “No more reality!” [6]

From a local perspective, as a starting point in search of the (as yet non-existent) Museum of Contemporary Art in Bulgaria I would like to take a discussion that “almost” took place – an arena for desires and decisions. Today we are in a unique situation in which there is an increasing opportunity for parity, because the collective desire is in itself a rather promising beginning, let us call it the politics of desire [7] – a politics of shared responsibilities. The desired discussion itself would constitute a step forward – a display of the processes of a social, political and cultural shift. Another discussion would then have a chance to come to the surface, concentrated around the design and nature of the future museum of contemporary art. An imaginary Museum of Contemporary Art in Sofia, a (potential) future democratic, dutiful artistic institution about to meet its presumed public.

“Тhe emerging question is: how can democratic art institutions that resist current political shifts be formed and established?” [8] In this concrete Bulgarian case we are faced on the one hand with the collective troubles and desires of the community of curators and artists dealing with contemporary art, to establish themselves, to constitute themselves in the social and cultural sphere in contemporary Bulgarian society. It must be noted that the art community is truly struggling with the ever dominating conservative and outdated prejudices in order to prove the value of their work as an important social and cultural commodity in an environment dominated by the newly-formed neoliberal market and the new political conditions. On the other hand, in this process a powerful force is at work, imposed as official politics on the public institutions for integrating the Bulgarian cultural sphere in intercultural exchange and in the new European standards. Through the pressure of this politics linked to the standards imposed by the European Union, the official political institutions should finally have no choice but to become interested in developing structures and favorable conditions for contemporary art. At the very least recognizing it as a cultural strategy for overcoming marginalization, as one possible ambassador of local culture in the international world of art and the European culture scene. [9] In spite of this, this interest has not been declared part of an official cultural politics, and the corresponding institutions do not look prone to overcome their thinking on culture and art in categories of the national and marginal.

In this barren landscape of culture-political ruins, a number of new art institutions have emerged, many of them initiated by artists, who have developed a variety of strategies for economic and artistic survival. They each represent their own nature of production principles based on international standards and polyphonic artistic practices across international art world networks: Interspace, the Institute for Contemporary Art, the Art Today Association, the Red House and numerous others. They have each expressed their desire for setting up a public museum of contemporary art, but have not managed to involve all others in a closer examination of how to shape a discussion that could lead to new visions, to an understanding of the design of this future public museum of contemporary art in Bulgaria.

Besides the existing interested institutions, such a discussion would need to include museum experts, curators, artists, as well as the media, sociologists, economists, philosophers, politicians, architects, urbanists, citizens, funding institutions. A discussion in a broad multidisciplinary framework of influences and interests in a broad field of reflections and social interactions in which relationships will give rise to a different format: working seminars, round-table discussions, research projects, panel discussions, exhibitions, local and international conferences, consulting with experts, the creation of a temporary body that could push this process ahead, but would at the same time guarantee a democratic approach and social dialog. Even if no possible and adaptable result may be lingering on the horizon, merely raising the questions should in itself change the situation in a positive direction: How can a debate be created in such a way as to express the broadest range of interests and issues, in order to allow us to start thinking of the future museum? What type of institution should it be? How should a future public museum of contemporary art in the Bulgarian capital be structured? Whose interests should it represent? What should be its representative functions, what its functional logic?

There are very different points of view about the museum as such. Especially over the past fifteen years, with the global changes in the economical and political conditions, the notion of the museum and its functions has undergone dramatic and dynamic changes. The interaction of the museum with the past and present have changed with the collapse of the hegemony of the white, colonial and national perspective with its symbolic hierarchy. The museum can no longer be static, and under ever growing economic pressure it has to remain competitive in the arena of entertainment and the spectacle of mainstream culture by discovering ever new ways of interacting with its public, with art, with different historical perspectives continuously being reinterpreted, and by producing ever new exotic images and allows for the social integration in various movements, communities and identities. Today the visitors of the big museums of contemporary art around the world are not only recognized, but also more and more treated as a new class of global consumers. Consumers for whom the buying of goods, as well as objects, and of ideas in the form of education and information, is a passion, a means of proving yourself and of being.

At the same time, various museums follow different strategies, politics and functional logics. We have in front of us a broad range of existing natures, philosophies and interactions. We could think of a comparison between the politics of the Whitney Museum, [10] The New Museum [11] and MoMa, [12] all three in New York. Each of these art institutions has developed from a different political, cultural and economic background in the same urban environment; each deals with its own context; each follows its own research path, its own reflexes and representations of global and local artistic processes; each seeks its own dialog with its public, its own social responsibility.

Transforming the history and value of art and art objects and ideas from different perspectives, radically dealing with museum hierarchies, the power of cultural norms of the existing institutional matrix, and issues of spatial relations, historically it has been easier to artists and curators with their subjectivity and obsessions, speculative philosophies, inner museums, a reinstalling or shift in perspectives, irony and political audacity to develop critical artistic strategies for criticizing museum institutions, than it has been for the institutions themselves. This specific approach is the institutional critique imposed from Duchamp and Piccabia through Jeff Koons and Haim Steinbach, who look at a critique of consumption, of commodification and the order of the art object, or curators like Harald Szeemann [13] or Nicolas Bourriaud, who have revolutionized the contemporary perception of the function of the museum as a space and arena for arranging artistic, visionary and cultural hierarchies, to Hans-Ulrich Obrist and his ideas on the Imaginary Museum.

Today along with enraptured fascination for these approaches, there is a tendency to think that the “institutional critique” of the 70s, 80s and 90s has been fully incorporated in the art institutions. And indeed, for various reasons today’s institutions have succeeded in getting used to themselves producing or imposing on themselves to actively participate in the process of producing contemporary art changes. It is a fact that in most cases, approaches connected to “institutional critique” have turned into an integral part of the institutions themselves: “institutional critique proved to be a method rather than a genre. Today a critique is no longer put up against the institution in order to deconstruct it.”

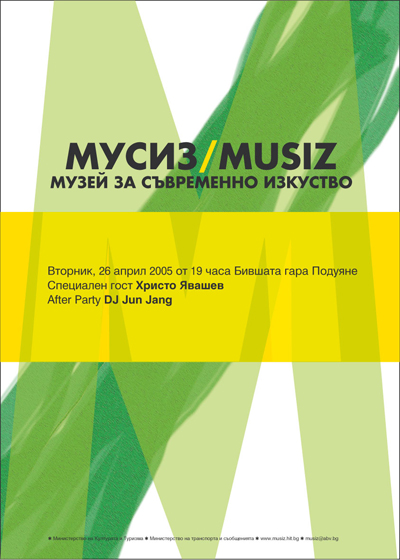

Ivan Moudov, representative of the second wave of Bulgarian “conceptualists,” over the past few years has concentrated his work mainly around approaches connected to “institutional critique,” in a series of works like “Fragments,” “MUSIZ,” and “Audio Guide.”

Poster for the Contemporary Art Museum “MUSIZ” action. © Ivan Moudov

This time “institutional critique” comes as the clever tactical intervention of an artist in the public urban space of Sofia: “Museum of Contemporary Art, Sofia,” in 2005. Ivan Moudov is the one who launches the debate and succeeds in grabbing the attention of the art community, but also of the media and cultural institutions, even sending a humorous wink to a broader young audience. At first “MUSIZ” develops as a media fake, to find its climax in the fake opening of a phantom museum. His action is extremely successful also in terms of the number of people he got together for the fake opening in an abandoned train station, an appropriate building in a modern industrial style which originates in the beginning of the last century. And he manages to attract sensational attention to the issue.

Billboard advertising for the Contemporary Art Museum “MUSIZ”, in the urban context,

part of the PR campaign before the opening action. © Ivan Moudov

After Moudov’s action it seems that a serious discussion about a future museum of contemporary art has become more likely on the horizon. The artist uses the action principle of the mirror held to the local context, or the mechanism of “subversive affirmation.” [14] He does not make any attempt at idealizing or at providing solutions, but rather works with existing discourses by multiplying them. He overlays many layers connected to local marginalizations, stereotypes, prejudices, or outright resistance against any kind of change. The perception of contemporary art in Bulgaria in some cultural groups can be described as xenophobia. [15] He plays with the public arguments between Cyrillic and Methodic (a popular designation for the Latinized version of Cyrillic as used in electronic mail, alluding to the brothers Sts. Cyril and Method) separating society in pro-Russian and pro-Western. Another layer relates to the internationally famous artist of Bulgarian origin Christo, by his civil name Hristo Javashev, playing with the fact that Christo cannot be considered a Bulgarian artist, having left the country many years ago and having worked in an entirely different context. [16] If you read the Methodic text on Moudov’s billboard, what you see is Christo, MUSIZ and the DJ Party. Surely the artist has accurately calculated the local, provincial effect of his action, and has put it to ironic use. Even as a true “guerilla” action enacted according to the rules of the genre, the intervention remains closed in the provincial circle of Sofia. And yet, the qualities of this work go far beyond the marginalized boundaries of the artistic and cultural space in which it plays.

“Opening” of the Contemporary Art Museum “MUSIZ” at the Podujane train station, Sofia. © Ivan Moudov

In fact the veteran of this approach in the Bulgarian art scene is Nedko Solakov. For years he has been working in the direction of “institutional critique” – an approach that has become essential to his work. Amidst a long list of projects realized by this artist predominantly for large museum institutions, decisive events and important private spaces of the art world, I will mention: His one-person show “Leftovers – a selection of my unsold pieces from the private galleries I work with” 2005 at Kunsthaus in Zurich, “Art & Life (in my part of the world)” 2005 at IXth Istanbul Biennale, “A (not so) White Cube” 2001 at P.S., New York. I’ll dwell only on two installations which are directly connected to the local scene of contemporary art. If they have not played the role of a driving force in the events, they have at least broadened the horizon. They have carried the smell of gunpowder and have been a bombastic celebration for this scene. Both installations can be regarded as true “little” conquests, and both will stay as valuable in the “archive” of those having achieved real “historical” value.

Installation view Nedko Solakov at Kunsthaus Zürich, 2005. Photograph: Arthur Faust, © Kunsthaus Zürich

“Les aventures (et les visions) de François de La Bergeron en terre Bulgare,” [17] French Institute, Sofia, 1993. The narrative in this installation is seen and told from the point of view of an imaginary traveler who crosses Bulgaria in modern times (before socialism). He is the emblematic figure of the Western observer of exotic places from the modern era, whose attention is grabbed by everything found on his path that does not hint at the “modern cultural achievements” of the locals. Solakov plays on the one hand with a reversal of perspectives and dislocation in order to underline the contradictions in the action of the mechanisms and their reflection in the value systems. On the other, he proposes an ironic criticism both of anthropological stereotypes for describing the customs and values of people through objects of everyday life, and of ethnographic stereotypes. At the same time this criticism is ironically directed at himself and the local “armored” understanding of national value and its construction based on the “disdained” folkloristic and mythological peculiarities. To this aim the artist introduces in his installation two works by Bulgarian masters, a portrait by Zlatyu Boyadjiev from his own collection and an Ivan Angelov borrowed for the occasion from the National Art Gallery. By including them as ethnographic objects in the general installation, he raises the question of their artistic value, turning these old masterpieces into their own cultural parody and raising the dilemma: “ethnographic” or “art” object? In another project for a radical action in the local context, which did not materialize (because of his parents’ firm opposition to such vandalism), Nedko Solakov intended to “transform” seven drawings from his collection of classics by scribbling on them, painting over them, writing notes all over them and such, outright “desecrating” them by his intervention – while at the same time we can safely assume that after their “transformation” they would be brought back from their life as ethnographic objects to fascinate the world of art, this time as pieces of contemporary art, and become attractive to the international art market and art world. Their significance would finally cross beyond the boundaries of the local context. The artist questions the hierarchical system for attributing economic and artistic value in the national art-historical context and the speculative art market showing faintly on the horizon. This is happening at the beginning of the 90s, a period in which the Bulgarian “old” masters were being sold at exuberant prices on the deeply local art market in Bulgaria due to speculative games and schemes for money laundering, whereas they had no value whatsoever on the international market. [18]

The principles of this case of a temporary local speculative art market bubble can be seen at work everywhere in the global world of art. This process is marked not only by post-colonial discourses such as “westernized by European influence” mixed with simultaneous oversize feelings of local greatness and inferiority. Not only from an Eastern perspective can the “sad” fate of a large part of the artistic heritage of locally important “classic” works of their authors be told. Works which after a time will provoke the interest only of a narrow group of specialists and historians or mean nothing to anyone any longer. It is a well-known fact that the future sometimes plays bad jokes in the world of art, regardless of geographical location.

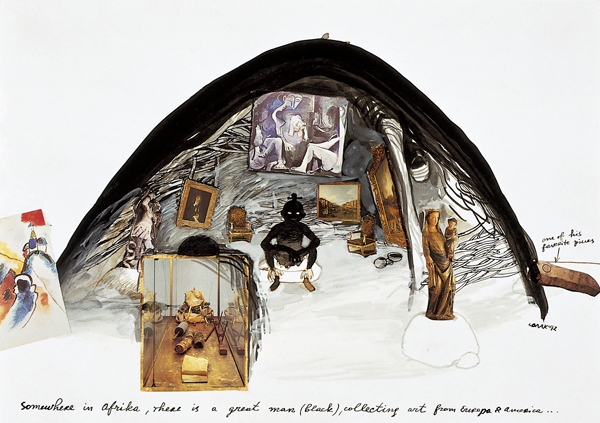

The Collector of Art, 1992. Watercolor, ink, collage on paper, 21 x 29 cm. Collection Lubinus © Nedko Solakov

Another “historically” important installation critical of institutions and the art world defined by the hegemony of the Western universalistic model, but also containing a hint of its own “absurd” situation, concerns the story of an artist selling and exhibiting in the West while living in the South-East: [19] Nedko Solakov’s “The Collector of Art (Somewhere in Africa there is a great black man collecting art from Europe and America, buying his Picasso for 23 coconuts...)” 1992-2005, shown among other places at the Museum Ludwig, Budapest, 1994. [20] A black collector of contemporary art from Europe and America is living, together with his collection, in a hut in an African desert. Solakov makes use once again of his favored approach of displacing perspectives in order to obtain absurd narrative constructions and catch an unusual view on objects and people. [21]

It looks like the idea of the future museum of contemporary art is on its way to being shared between the three old art “super” institutions that have come about as “historic,” “national,” or “foreign” museum venues from the dawn of the new Bulgarian state through the end of the 19th century to late socialism: the “Sofia Municipal Art Gallery,” the “National Art Gallery” and the “Bulgarian National Gallery for Foreign Art.” As time proceeds, the idea that each of these existing museums broaden the interests of its collection and provide for the creation of a new department from which at a later point the new museum could branch out, is becoming more realistic.

The director of the National Art Gallery, Boris Danailov, has serious ambitions to define a new kind of politics and to find a new approach to the local art scene and contemporary art. In an interview with the Bulgarian Diplomatic Review [22] he expresses a position that is new for this institution: “Now, it is more future-oriented.” A new political course, a renewal and modernization of this public museum institution. The director announces that he is opening the doors wide for new “artistic styles and genres.” He underlines the historical connection between the past and the present, and how the initial department of the museum, founded in 1892, also started out with gathering works by the then-contemporary Bulgarian artists. [23]

The National Art Gallery is showing real appetite for the idea of a future museum of contemporary art as an offshoot of its own institutional body. The Gallery turns out to be a true driving force for this process, as it organizes the first auction of contemporary art in Bulgaria in order to create the initial collection of the “future museum” of contemporary art. If the aim of this auction was to concentrate exclusively on the commercial side and the development of an art market for contemporary art, this could count as a true achievement. But I feel ill at ease thinking of a commercial auction as a positive starting point for a discussion on a museum – even if it takes the guise of a charitable event. As Minister Stefan Danailov, namesake of the aforementioned Boris, declares in his speech: “The accumulation of the initial permanent collection out of the sale of the works themselves is of groundbreaking importance for laying the foundations of the new museum.” [24] The most important thing, we are told, is to make the first step – and the rest will follow. Why are things once more lumped together, and the official institutions find themselves again with strange political strategies? A question arises from the initial collection thus raised for this “future museum of contemporary art” – what is the role of the state and public institutions, and what is the role of the free market in a democratic society? Applying this recipe would result neither in a real art market nor in a really public museum of contemporary art.

When you are in an isolated space, the local truths are privileged. Not one of the official art museum institutions is proposing an approach with which to face the facts – which remain largely terra incognita to the Bulgarian institutions. In search of a discourse more adequate, on an institutional level, to ongoing processes in contemporary art, we might want to dwell on the arguments put forth by Ruxandra Balaci, the scientific director of the recently formed National Museum of Contemporary Art in Bucharest, located since 2004 in a wing of the monumental and infamous former House of the People, on the aims of this new museum. [25] Beyond dialog, interactivity and experiment, she speaks of a museum in progress, of the importance of the international board in achieving legitimacy in global processes, but also in providing a steppingstone for Romanian artists and curators to events and processes on the international scene. She discusses the difficulties of maintaining institutional and financial autonomy, of explaining to a majority of politicians who “do not make the difference between contemporary and modern art” the importance of flexible structures for a museum of contemporary art, of functioning like a research lab, in permanent movement, while keeping in mind social realities on the ground, the absence of money and a “culture of mediocrity” generally sustained by the media, against which the local PR of a museum in progress, whatever its achievements in the eyes of international observers, has a difficult stand.

In contrast, on the Web sites of the three established Sofia museum institutions, embedded in bad design and fraught with bad navigation, we cannot find any indication of the existence of a board, a lobby, patrons, members, funders. [26] This does not come as a surprise: As far as I am aware, none of the existing museums is structured according to such principles. No program of upcoming events is published; no educational activities are proposed to the public; references to their publications are lacking as well as specific information about the different departments. The one partial exception is the Sofia Municipal Art Gallery, which makes an attempt at providing extensive online documentation of its past events and exhibitions, as well as a detailed description of its structure and the history of the museum.

In a situation like this, which can be described rather as a power game between the state institutions of art, than as a differentiation into specific institutional political strategies, the question is which one will dominate over the others and swiftly redefine its position to become the venue of choice for contemporary art according to global standards. The Sofia Municipal Art Gallery also has started organizing its own permanent collection of contemporary art. What is more, in a specific local cultural and social context dominated by the lack of money and the haunting specter of the state bureaucracy, the museum presents itself with an outright “dynamic” approach towards representing contemporary art. Thanks not only to its team, but also to the long-standing efforts and personal interests in curating contemporary art of the main curator of this art institution Maria Vassileva, with her experience gathered as an independent curator both in the local and in the international art scene. Among her multiple small and clever or more sizeable efforts at opening more space for contemporary art, the series of exhibitions “Meeting Place” stands out, with its one-person shows of young artists and curators who have recently made their appearance on the art scene. Some of these for the first time receive an opportunity to work in a museum venue. The project is based on a model that is unique in the Bulgarian art reality and among local institutions – the museum as a laboratory, [27] as an open place for meetings and discussions, the museum as a bridge between generations and between different audiences. It is also the only museum venue where you can find some kind of a professional archive and information on Bulgarian contemporary artists. Unfortunately, in spite of this compelling evidence of readiness to change this art institution, it remains dominated by its past and the lack of a legal framework provided by the corresponding ministries and the municipality.

Another interesting project attempting to establish, using a clever approach, “new” names in the conservative local historical and museum context, again at the Sofia Municipal Art Gallery, with curator Maria Vassileva: “Sofia Municipal Art Gallery and Group 8th March present: Reflections Multiplied, curated by Maria Vassileva, 2006.” The exhibition does not look so much at issues of visibility vs. invisibility, or attempt to discover “marginalized” authors. Rather, the aim is to show on a par, without hierarchies, contemporary art works of contemporary women artists who have made a career on the local and international scene, in the midst of works of art that have acquired “national value,” by women artists of the beginning of last century, names recognized as “classics” in the history of Bulgarian modern art. And through this search for a historical connection to the roots of women’s art in the Bulgarian art scene, to attract the attention and convince the local audience of the meaning of contemporary art in the context of this history. In other words, to corroborate the value of the contemporary art of these women artists as “national heritage.” The truth is that the names selected for the exhibition of the contemporary women artists are much less “marginalized” than their “historical” representatives. With their art they speak a global language, much more adequate to the context of the international art scene, politically and socially engaged. In fact the exhibition is quite political and has opened up a discussion on “how art fights for its visibility and effectiveness in society today.” But with the ironic displacement of perspectives imposed by the specific local context on this set of issues related to the socio-cultural relevance, the place, the role and the value of art in a contemporary society. Because its “classic” representatives do not have any other chance but for their art to become of local artistic significance. Whereas the contemporary women artists may even stand a chance to be “really” discovered by the international art market or the big and defining museum spaces and events.

The project Artspace: Summer 2006 points in this direction of overcome pessimism, as “a bite of optimism – there are a few symptoms of ‘normalization’ of that process,” [28] – a real step forward. The project was part of the “Critics’ Selection” cycle, a forum for critical discussions on contemporary art aiming to promote young authors working in Bulgaria. It was initiated by the young curators Iana Kostova (an art historian) and Vladia Mihajlova (a cultural scientist). Together with students and lecturers at the Art Academy in Sofia, the curators temporarily settle down in the studios of the Art Academy, in ruins and non-functioning, at the very center of the city on Dondukov 56. The project consists of three parts: workshop, exhibition, and discussions. In a text by Iana Kostova discussing at length the art event, [29] the author claims that the project reflects on the problem of the lack of space for contemporary art and aims at contributing to its happening and being created and imagined in Sofia. Fascinating is the understanding that an essential approach to resolving the problem lies in a discussion around an imaginary venue. The project, as far as the resources at hand allowed, analyzed the past and present, looked carefully at the past attempts, most of them transitory and short-lived, to form non-commercial, alternative gallery spaces and centers for contemporary art. Perhaps as a step forward towards finding a new, better solution. Which without doubt the modeling, structuring and existence of a public museum of contemporary art would be. A museum of contemporary art which of course will guarantee the possibility of a long-term culture-political strategy in this realm. “In this sense the idea of the summer edition of the Critics’ Selection is to attempt to give life to one possible (though utopian) micro-variant of a hypothetical art space, which is to be different, where things are to happen even when the money is lacking, even when there is no developed infrastructure or culture-political strategy to support contemporary art here. The focus of the project is an absence.” [30]

In the times of disciplinary society analyzed by Foucault, Deleuze and others, the museum is one of the institutions with walls, alongside school, the prison, the family. Following a crisis of its institutions, disciplinary society reforms itself into a society of control. Like the other institutions in decay, the museum ends up being everywhere, now functioning as a producer of discourses. Paradoxically, after a phase of experiments, this process leads to a concentration of power that makes it difficult for independent approaches to survive: “The tendency is clear: centralized superstructures are encouraged – Tone Hansen uses the term “megamonstermuseum” in her study of the centralization process of the state museum in Oslo.” [31]

Against the overwhelming power of the economy of scale, why not propose a museum without its own collection? Why is it expected of this non-existent museum that it once again represent and sanction the national? Why not a museum that does everything possible in order not to exclude an audience that does not follow and enact bourgeois ideas of prestige, in order to avoid being elitist and serving only global consumers? A museum open to populist conceptions of public space, which fetches people where they are.

We might seek inspiration in small models of alternative museums like the “museum in files” Lia Perjovschi has been working on over the years, and of which I recently had the pleasure of seeing a variant at the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich, in the context of the exhibition “Dada East – The Romanians of Cabaret Voltaire.” Also known as the CAA, the Contemporary Art Archive (and at the same time the Center for Art Analysis), this chronology is a “non-institutionalised art archive, … a space for contemporary art and critical attitude. Data base (international) focusing on art theory, cultural studies, and critical theory. Comprehensive collection of slides, video tapes, CD, catalogues, books, reviews, documentation of international art and cultural events… An exercise for dialogue, communication, empowerment, natural relation. Themes, reflecting the current discussion in the art field and new cultural theories. Issues about social and political relevance of art, the autonomy and context of art. From one to one dialogue to group discussions, lectures, presentation, workshops, exhibitions,” extending into real space, into Lia Perjovschi’s own studio and other spaces, to involve people in thinking critically about art. [32]

[1] Jenny Holzer: Multiple. Glass sphere with engraving. (2000) CHF 2000. On sale by Art Forum Ute Barth, Zurich. Kunst Zürich 06. 12th International Contemporary Art Fair. ABB Hall 550. Zürich-Oerlikon.

[2] Dan Perjovschi, Key Words in the New Europe, in: Marius Babias (ed.), The New Europe. Culture of Mixing and Politics of Representation, Generali Foundation, 2005, p. 139.

[3] Pessimism No More! is a work by Pravdoljub Ivanov, Bulgaria, 2002. Billboard (dimensions variable). Part of the group show “Bound/less Borders,” Belgrade, Yugoslavia; Cetinje, Montenegro; Bucharest, Romania; Vienna, Austria (concept of the show: Biljana Tomic). In this work, Ivanov covers with band-aids the famous holes of real pieces of Swiss Emmental cheese, produced since 13th century in the valley of the Emme river, “fixing” what the producers consider a proof of quality. The Emmental cheese is surrounded by an entire culture of feeding the cows, production of the cheese with three types of selected bacteria, ageing, quality control, advertising all the way to the consumption with well-defined types of red wine.

[4] From Guy Debord’s revolutionary ideas on the Society of the Spectacle <http://library.nothingness.org/articles/SI/en/pub_contents/4> (visited 12 January 2007) to the academic cultural studies efforts on how the West produces exotic images. E.g., Angela McRobbie (ed.), back to reality? social experience and cultural studies, Manchester University Press, 1997.

[5] Cf. Nicolas Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics, les presses du réel, 2002 (1998).

[6] Philippe Parreno, short video, 1991: fake street demonstration, children marching with the slogan “No more reality!” on banners. Cf. online <http://www.airdeparis.com/pnom4.htm> (visited 12 January 2007).

[7] A term dear to Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari.

[8] Nina Möntmann, Art and its institutions, in: idem (ed.), Art and its institutions. Current conflicts, critique and collaborations, Black Dog Publishing, 2005, p. 8.

[9] “Contemporary art has never been so popular – but what is its role today and who is controlling its future?” Julian Stallbrass, Art Incorporated. The Story of Contemporary Art, Oxford University Press, 2004, on the sleeve.

[10] Cf. <http://www.whitney.org/www/collection/history.jsp> (visited 12 January 2007). Although the Whitney’s acquisition budget was always rather modest, the Museum made the most of its resources by purchasing the work of living artists, particularly those who were young and not well known. It has been a long-standing tradition of the Whitney to purchase works from the Museum’s Annual and Biennial exhibitions, which began in 1932 as a showcase for recent American art. A number of the Whitney’s masterpieces came from these exhibitions, including works by Arshile Gorky, Stuart Davis, Reginald Marsh, Philip Guston, and Jasper Johns. Even today, the Museum continues to enrich its Permanent Collection via the Biennial; among the recent acquisitions are works by Mike Kelley, Matthew Barney, Louise Bourgeois, Zoe Leonard, Matthew Ritchie, and Shahzia Sikander.

[11] “Being a board member of a successful institution is attractive as social status, yet we don’t want a board that believes the institution could be undermined through too much experimentation or radical positioning. The New Museum was founded by a curator (a rare among museums) on the premise of curatorial entrepreneurship, which should continuously redefine itself. That’s the philosophy of this museum and it’s why we don’t have a big collection.” Carolee Thea, Interview with Dan Cameron, in: Foci interviews with ten international curators, apexart curatorial program, 2001, p. 107. It is in the venue of The New Museum, founded in 1977, that a number of artists have exhibited for the first time in a museum environment, such as Carolee Schneemann, John Baldessari, David Wojnarowicz, after they had no possibility ever to work with a large and official institution before. Others, like Martha Rosler and Adrian Piper, had their first retrospective there, and some were discovered for the international world of art through their personal shows or participation in group shows at The New Museum <http://www.newmuseum.org/> (visited 12 January 2007).

[12] “Founded in 1929 as an educational institution, The Museum of Modern Art is dedicated to being the foremost museum of modern art in the world.” From the official MoMa website <http://www.moma.org/about/> (visited 12 January 2007).

[13] “Following the brouhaha of Documenta 5, Szeemann retired to Ticino and there invented his own profession as an independent exhibition maker. In a spirit of pataphysical enterprise, he founded the “Agency for Spiritual Guest Labor” as a subsidiary of the (imaginary) ‘ Museum of Obsessions.’ ” Tobias Bezzola, Natural Pathos. Harald Szeemann (1933-2005), Parkett No. 73/2005, p. 175.

Szeemann referring metaphorically to Marcel Duchamp: “Of course you have inner rules, like a museum of obsessions that is in your head. Then there are the freedoms or constrictions that we have from place to place.” Carolee Thea, Interview with Harald Szeemann, op. cit., p. 18.

[14] Cf. for instance Dimitrina Sevova, Sparks from the Interaction between Art and Politics in Zurich, Umělec 2/2006 <http://www.divus.cz/umelec/article_page.php?set_lang=2&item=1268> (visited 3 May 2010).

[15] “In retrospect, that chapter in the history of contemporary art in Turkey was all about xenophobia. Contemporary was alien, folks like me were aliens, the Biennial was alien. The thing is that this modern, elitist, provincial mafia used to think they were in the same league, but they’re not. It’s like the galleries on West Broadway in New York, which sell these things called “art” to gullible tourists.” Carolee Thea, Interview with Vasif Kortun, op. cit., p. 57.

[16] “In April this year Ivan Moudov “opened” the Museum of Contemporary Art in Bulgaria. The main focus of the broad campaign was the name of Hristo Javashev used as a media bait. Successfully, as it turns out. Not by accident, either. The fiction, the lie, the space that turned out to be empty at the Podujane train station is not another trick in a lying competition, but a question, which however carries its own answer – one of the possible answers. Not just because we do not have. We do not have because we are not clear as to what contemporary Bulgarian art is. Is it Bulgarian at all? And what does Bulgarian mean in the end?” Vladia Mihajlova, Hristo or Christo, Kultura No. 43, 9 December 2005 <http://www.online.bg/kultura/my_html/2393/christo.htm> (in Bulgarian; visited 12 January 2007).

[17] The title of this exhibition is everywhere quoted in French. In English: The adventures (and visions) of François de La Bergeron on Bulgarian lands.

[18] The following comparison imposes itself: “At that time the local reaction to an international exhibition was stronger than now. There was a provincial market with its products and collectors. Local powers were much stronger, you see. Beral was chastised, as I would be later on. That was the late 80s and many dictatorships were dying or fading away, mutating into neo-liberal political systems. There was a lot of money around and a boom in provincial collections. The [Istanbul] Biennial intervened in this social space and problematized it, even though it had been an agent of the neo-liberal economy.” Carolee Thea, Interview with Vasif Kortun, op. cit., p. 56.

[19] “Here in Budapest, in 1994, working with one of my favorite curators, Katalin Neray, I did one of my favorite projects, “The Collector of Art,” about the great black man who lives somewhere in the African desert and collects contemporary art from Europe and America, buying his Picasso for 23 coconuts, or his early Rauschenberg for 7 antelope bones. Katalin was generous enough to let me use most of the masterpieces from the Ludwig collection to place them into the black guy's hut.” Nedko Solakov, A bitter text that ends in a joke, in: Dimitrina Sevova and Alain Kessi (eds.), CFront Book – Crossing Points East-West, cflow, 2002, p. 91. Available online at <http://www.cfront.org/cf00book/en/nedko-bitter-joke-en.html> (visited 12 January 2007).

[20] The Bulgarian public met with another version of this installation in the exhibition “N Forms? Reconstructions and Interpretations,” 1994, SCA/Raiko Alexiev Gallery, Sofia. This Annual Exhibition of the Soros Center for Contemporary Art remains to this day the most thorough investigation and representation of the “Bulgarian avant-garde” and perestroika of the mid-80s, which outlined the new artistic practices and its discursive grounds on the Bulgarian art scene.

[21] Another critique of the mechanisms of the production of exotic images, imposed along with all stereotypes by an overblown entertainment industry, from an Eastern perspective is found in a text by Ekaterina Degot: “[The Westerners] consider Russia an exotic rather than a western country, despite the fact that Sophie Marceau played the role of Anna Karenina.” Ekaterina Degot, Lecture at the Opening of the Exhibition “So Far, So Close…” by Olga Kisseleva, in: Passage Europe. Realities, References. A Certain Look at Central and Eastern European Art, Musée d’Art Moderne de Saint-Etienne Métropole, 2004, p. 154.

[22] Of which the following excerpt shows a bold attempt by Boris Danailov to quote Harald Szeemann and sound adequate to the global processes: “There is a very interesting place on the Gallery’s ground floor – the Chapel – where exhibitions are also organized. But these are a different type of exhibitions. If the ones organized upstairs are representative, more serious events, down here we guarantee liberty and diversity of the presented authors – some of them are budding young artists, others offer an alternative form of art and there are also artists who want to show something new. We are after a more dynamic rhythm, trying to keep our fingers on the pulse of today’s life. What is happening in the public space is also happening here. Thus, the Gallery appears as an active partner to the art of today.” Antonia Vitanova, The National Art Gallery, Bulgarian Diplomatic Review, available online at <http://www.diplomatic-bg.com/c2/content/view/987/47/1/0/> (visited 12 January 2007).

[23] This is ignoring the fact that more or less around this time the first Bulgarian artists to really create works make their appearance, creating something that in form and content can be recognized as fine arts. This process comes “monstrously late.” On these territories, part of the Ottoman Empire, no “worldly paintings” or fine arts are produced or created. The iconography is that of canonic church painting, created by anonymous masters, and is the only widely accessible notion of this type of art until the beginning of the 19th century, when the concept of the author is imported to these territories from the West along with that of the nation-state. That is how the first true artists and their great works appear on the scene, branded by the fact that they are truly the first in a history. The truth is that after the new modern Bulgarian state was constituted, the deficit in local artistic talents led the forefathers to import them from Slavic lands more advanced in their development. The artists invited from the Slavic border regions of the Austro-Hungarian Empire or from Russia were provided by the state authorities with studios, official positions, grants and other attractive offers to make them stay and fulfill their grand mission – to lay the foundations of a Bulgarian art scene. A story reminiscent of that of the new Bulgarian Czar, imported around the same time from the West, along with Brussels needle lace and other fashion attributes brought in to substantiate the glamour of bourgeois ideas of prestige.

[24] You can get a direct impression of the speech of the Bulgarian Minister of Culture, Mr. Danailov, at the first auction of contemporary art in Bulgaria on 19 December 2006, online at <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GiRAuhRdAFo> (in Bulgarian; video has since been removed).

[25] Cosmina Ionescu, Interview with Ruxandra Balaci, in: Observator Cultural, No. 220. Available online in English translation at <http://www.mnac.ro/interview.htm> (Romanian original text at <http://www.observatorcultural.ro/infoframe.phtml?xid=10976>; both visited 12 January 2007).

[26] In fact, the websites of two of the institutions mentioned, reachable less than a year ago, are currently offline.

[27] Hans-Ulrich Obrist: “Alexander Dorner’s importance lies in his innovative definitions of the museum’s role: the museum in a state of permanent transformation; the museum as oscillating between object and process; ….” Hans-Ulrich Obrist, dontstop, Sternberg, 2006, pp. 54-55.

[28] Nedko Solakov, op. cit., p. 90.

[29] Iana Kostova, Art as if for the last time, available online at <http://www.liternet.bg/publish19/yana_kostova/izkustvo.htm> (in Bulgarian; visited 12 January 2007).

[30] “Another category is an exhibition where the visitor doesn’t have to come to a place to see it, the museum is both actual and virtual. This would lead us to the Viennese Museum in Progress, which organizes exhibitions in the newspapers or produces Boetti’s puzzles, which are distributed on the airlines.” Hans-Ulrich Obrist, op. cit.

[31] Nina Möntmann, op. cit., p. 13.

[32] Cf. the chronology online at <http://www.perjovschi.ro/pdf_files/Detective_Draft_part5.pdf>.

This article was originally published in Vector Magazine 03/2006.